Innovation Alliance Blog Post: Setting the Record Straight For Smart Patent Reform

For those paying attention, Price Waterhouse Coopers (PWC) released an updated study on Patent Litigation several days ago. While many jumped to amplify the message of increased litigation by so-called “trolls”, the report unfortunately contained several inaccuracies and misleading data. In an effort to support well-informed policy making, those inaccuracies are clarified below.

- An overly-broad definition of NPEs

The PWC study claims that in 2013, NPEs (those who license or enforce their patents and who many deem as “trolls”) filed 67% of the total number of new patent infringement cases, up from 28% from 2009 (page 2, paragraph 3). However, PWC’s definition of NPE is rather misleading, clubbing together any potential “troll” with leading universities, individual inventors and currently non-practicing-firms which may have invented its own patents as a leading innovator (e.g. Nokia). In fact, the PWC report itself shows that Universities have a much higher patent litigation success rate than non-practicing-firms (see page 20, chart 11b).In fact, the share of NPE lawsuits has remained relatively stable for the past decade.

- Disregard for impact of 2011 AIA legislation

AIA legislation passed in 2011 forced plaintiffs to file separate lawsuits against each defendant. For example, a firm filing a patent infringement case against 10 firms, until September 2011, would show up as one single patent case. After the passage of 2011, that same suit would appear as 10 different cases. This report completes disregards the natural inflation in some types of lawsuits as a direct impact of this legislation and wrongly attributes that increased number to an increase in litigation activity.

This potentially explains why the results of the PWC report are so different from that of respected academic researchers who use the PWC data itself for their analysis. In their 2013 paper, Michael Mazzeo, a professor at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, along with his co-authors, published a paper “Do NPEs matter?: Non-practicing entities and patent litigation outcomes”, published in the Journal of Competition Law and Economics. In the paper, they explicitly show that the number of lawsuits filed by NPEs has never gone over 30% from 1995-2011, and that the share of NPE lawsuits has remained relatively constant (page 30, Figure 1).

- Omission of “patent quality” as a factor

A crucial question left unanswered by the PWC report is how patent quality is associated with patent damages. In the fair world of “may the best idea win”, if the better patents are commanding higher damages, there isn’t a problem with the patent system – it’s working. Better ideas should command higher damages when claims are substantiated. This isn’t bad news, its good news and reflective of American priorities.

The misleading results of this study were further compounded by an article in the Washington Post that took a graph from the study showing patent lawsuits and granted patents – on different scales – and imposed them over each other. This lead to a misleading picture of the litigation trend increasing, when in fact there has been little to no increase over this time period.

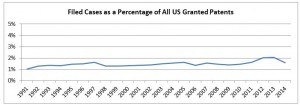

For a better understanding, a careful analysis requires putting the two trends on a common scale and comparing them. We did exactly that, by comparing the patents granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the patent lawsuits filed in US District Court (USDC; available through PACER) during the same periods of time. The graph below shows the patent lawsuits filed as a percentage of the patents granted in a given year.

The graph shows that the number of lawsuits filed have remained to be only between 1-2% of the total number of patents granted by the USPTO – hardly an “increasing trend”.

At the end of the day why does any of this matter?

For Universities, licensing is a vital source of income that allows them to continue funding research that drives important innovation. For individual inventors who don’t have the means to turn their ideas into products, it means the continued incentive to innovate and support for others to bring their ideas to life. For the U.S. economy, patent licensing has provided billions annually.

Universities, independent inventors, licensing firms and innovative research and development firms aren’t “patent trolls”. They are essential components of a thriving and globally competitive American innovation ecosystem. The future of economic growth and strength lies in our nation’s ability to create the innovations of tomorrow — 65 percent of today’s grade-school kids will end up in a job that hasn’t been invented yet.

Innovation is at the heart of America’s economic strength, and our patent system is the very innovation ecosystem that drives our nation’s economy.